Social distancing doesn’t come naturally in Israel. But the country, known for its informal, in-your-face mentality, seems to be setting a new standard for public protests in the age of coronavirus. During the past two weekends, thousands of people have gathered in perfect geometric patterns in Tel Aviv’s central square to comply with social distancing rules as they express their anger over the continued rule of a prime minister charged with serious crimes.

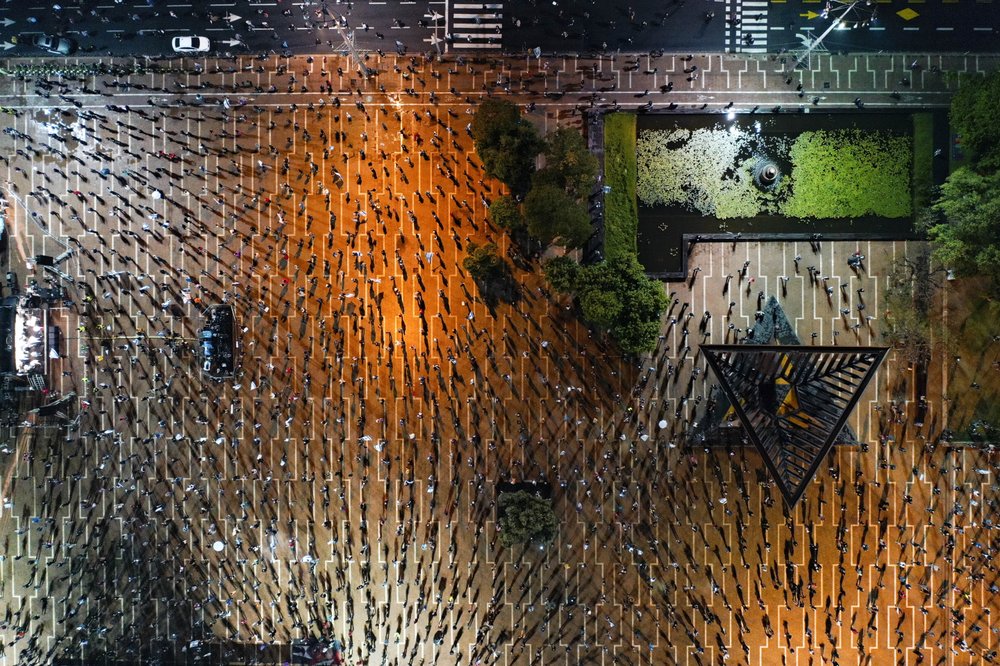

The demonstrations, resembling a vast glowing human matrix in stunning aerial photos, have become a symbol of Israel’s dueling political and health challenges. They also contrast with some other hot spots of civic unrest at a time when gatherings are restricted or banned around the world.

“If we want to succeed, we need to do it the right way,” said protest organizer Shikma Schwarzmann. “We obey the law.”

Civic protests are common in Israel. When the government imposed movement restrictions last month, it made exceptions for protests as long as participants stayed two meters, or six feet, apart.

Schwarzmann, a particle physicist at Israel’s renowned Weizmann Institute of Science, said she never intended to become a political activist but was galvanized by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s behavior. Many believe his actions, cloaked in the battle against the coronavirus, are really aimed at avoiding prosecution for corruption charges and remaining in power.

Last month, citing the coronavirus, Netanyahu’s hand-picked justice minister all but shuttered the country’s court system, postponing the prime minister’s trial until May. The middle-of-the-night order came just two days before the trial was to begin.

Days later, a Netanyahu ally suspended parliamentary activity, temporarily preventing opponents from proceeding with legislation that could have barred the Israeli leader from serving as prime minister.

In their first act last month, Schwarzmann, her three brothers and some friends organized what they expected to be a small protest convoy. As word spread on social media, the convoy grew to hundreds of vehicles, many of them stopped by police en route to Jerusalem. Demonstrators honked horns and waved black flags from windows but remained in their cars to comply with public health instructions.

In recent weeks, the grassroots “black flag” movement turned its attention toward the new coalition agreement between Netanyahu and his rival Benny Gantz.

Gantz, who had vowed never to sit in a government with Netanyahu, cited the coronavirus crisis for the about-face. While Israel has largely kept its outbreak in check, over 200 people have died and its economy has been ravaged as unemployment spiked to 25%.

The protesters have held three gatherings in Tel Aviv, with volunteers telling people where to stand by marking the ground with “X’s” carefully spaced over six feet apart from one another.

The X’s were the idea of one of Schwarzmann’s brothers, who brought a large box of chalk with him the first week. Activists have also held smaller demonstrations in Jerusalem.

The Tel Aviv protests have been vocal and visible. Participants wearing face masks hoisted Israeli and black flags, held signs reading “Crime Minister” and beamed their cellphone flashlights into the air for cameras above.

The demonstrators, estimated to be in the thousands, have been orderly. Police say there have been no arrests.

“It’s nice to have nice pictures, because it gives us exposure,” Schwarzmann said. “But this protest is not about beautiful pictures. The big picture in this country is not that beautiful. That’s why we are protesting.”

Protests in Israel are not always so mild-mannered.

Jerusalem market vendors barred from opening their vegetable stalls recently scuffled with police. In pre-pandemic times, demonstrations by some groups, including Arab citizens, Ethiopian immigrants and ultra-Orthodox Jewish men, sometimes ended in clashes, with police accused of using a heavy hand. In the occupied West Bank and Israeli-annexed east Jerusalem, security forces at times use lethal force against stone throwers.

Demonstrators in some other countries have struggled to adapt to the age of social distancing.

Russia has experienced some online protests, and anti-nuclear activists in Japan are encouraging people to protest on their balconies on May 9.

In other places, including southern Russia, Ukraine, the U.S., Germany, Lebanon and Somalia, protesters have flouted social-distancing rules.

In Hong Kong, which has banned public gatherings of more than four people, a few hundred anti-government protesters recently attempted unsuccessfully to split into small groups and were dispersed by police.

In Lebanon, hundreds of protesters set banks on fire and hurled stones at soldiers in riots triggered by a the country’s financial crisis that was exacerbated by a weeks-long virus lockdown. Earlier this week, a man was killed in clashes.

Schwarzmann said she does not expect to demonstrate every week, but that activists will continue to find creative ways to protest.

A group of business owners, for instance, plans another convoy this week to press for financial help, while a good-government group is organizing another Tel Aviv demonstration on Saturday in support of the Supreme Court, which is to rule on the legality of the new coalition deal next week.

“I don’t know if we will succeed. We will try at least to do things that have a chance,” she said.