“I survived as I was late,” she said. “So, yes, I know and feel lucky that I wasn't here at that time. But, thinking about those who were killed just because they were good and punctual, I am just so sorry and feel so bad for them.”

She remembers little about her co-workers, who were mostly men. The trauma of the bombing eclipses any memories she might have had of the weeks before it.

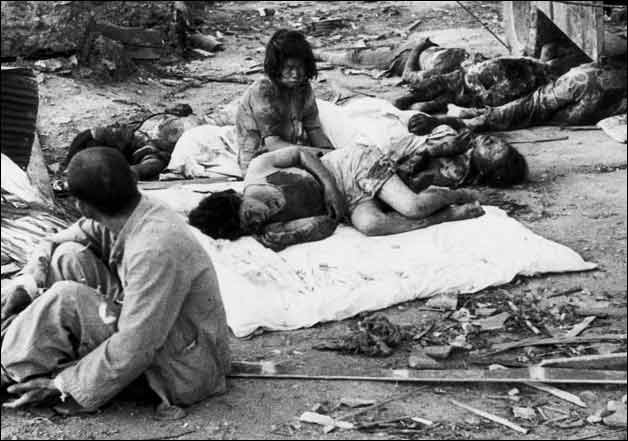

Although she escaped death, her face, arms and legs were burned; some scars are still visible. Her house burned down, she was bedridden for three months and she lost her father, who was believed to be at his office close to the epicenter.

Losing so much, the remaining family members left Hiroshima to rebuild their lives. Mihara met her husband in Kyushu, the island south of Hiroshima, and they had three children.

While many atomic bomb survivors, particularly women, found it difficult to marry because of fears their children would have birth defects, Mihara says her husband was so smitten with her that his mother didn't object. He died relatively young, however, and Mihara returned to Hiroshima, where she worked in a trading company to support her family until retirement.

In its postwar rebuilding, Hiroshima decided to conserve the dome as it was in 1961, leaving it as an icon of devastation in a city where such scars were quickly becoming invisible. The building was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996 to call for a non-nuclear world and world peace.

For most of the past 70 years, Mihara said little about her time at the dome. But as others of her generation passed away, she began to wonder whether it was her duty to speak - even whether that was the reason fate spared her. Now she shares her experiences more.

“I could have died in the bombing, but I am so blessed having survived to live such a happy life,” she said on a cloudy July afternoon.

She stopped at an inconspicuous memorial, mounted on the corner of the fence surrounding the dome, and kneeled to pray.

Kayo first visited Hiroshima on a school trip when he was 14. He listened to a survivor who told her story on the riverbank; he was struck by the scars on her neck and hands.

About a decade ago, he learned that debris from the dome could still be found in the river. He began searching for it, in part to keep the memory of the event from fading away.

“What I am afraid of is that it started to feel like something further from reality,” he said. “But here in front of the dome, everything is conserved as it was, and we can still find these relics from that time. In this way, I am trying to bring back the past to the present.”

He has retrieved shattered bricks and stones of various sizes. On many, the L-shaped motif that decorated the building is still visible, though much faded.

A few pieces are as big as a meter (3 feet) long, and had to be pulled out with a machine. Most are much smaller. Shells have attached to them after decades in the river.

Kayo has been allowed inside the normally off-limits building to compare its material and structure with the debris he has found. So far he's found about 1,000 bits of rubble that match.

There is no known research on how the debris ended up in the river, Kayo said. He suspects some of it was thrown into the river when people were trying to rebuild the city after the bombing, but he doesn't rule out the possibility that some was blown into the river by the blast.

He has sent pieces to more than 50 universities and institutions across the world as tangible evidence of the destruction. Though some declined the gift, about 20 accepted, including Stanford University and Cambridge. At Hiroshima University on Thursday, the 70th anniversary of the bombing, a representative of the Czech Republic, the architect's homeland, will accept the largest fragment Kayo has recovered so far.

Kayo's university also displays some of the debris at a small museum on campus. He has set up a nongovernmental organization and now has a few younger students helping him with the work. He's also studying anatomy as a Ph.D. candidate, to be prepared in case he finds the remains of A-bomb victims in the riverbed.

Each time Kayo looks for more pieces of the building, he bows to the river before he steps in.

“To me, the dome is a graveyard for those killed in Hiroshima, for those killed inside the dome, died nearby, died drowning in the river, those died at the field hospitals,” he said. “The place is a graveyard for all of them.”