In 2014, a spate of child-sexual-abuse cases in Bangalore gained much attention: A six-year-old girl raped by her 37-year-old teacher, a four-year-old girl sexually assaulted by unidentified persons and an eight-year-old girl raped by her 63-year-old teacher, to mention a few.

Splashed in the media and fiercely debated, these cases were only the public manifestation of what is increasingly acknowledged as a largely private crime, with unknown numbers not reported or registered in official statistics.

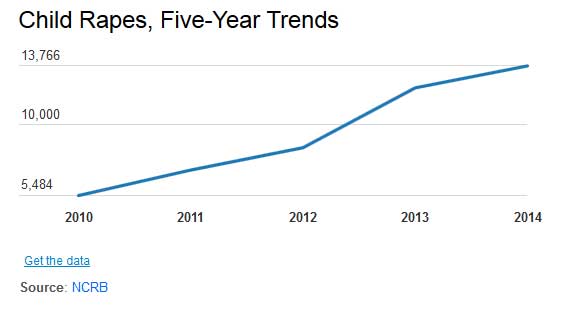

Yet, the number of registered child rapes rose 151% from 5,484 in 2009 to 13,766 in 2014, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

In addition, 8,904 cases were registered nationwide under the Prevention of Sexual Offences Against Children (POCSO) Act and 11,335 under the category “assault on women (girl child) with intent to outrage her modesty under Section 354 IPC (which includes stalking, voyeurism, use of criminal force with an intent to disrobe, etc)”, according to the NCRB.

NCRB has started collecting POCSO-specific data only from 2014 onwards only. A simple explanation of the POSCO Act is given here—the new law makes it mandatory to report all cases of child sexual abuse.

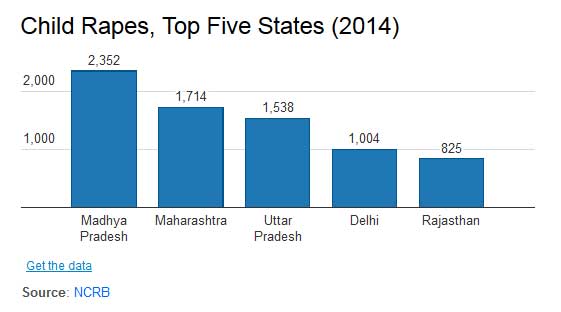

Madhya Pradesh tops the list in child rapes, followed by Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh (UP).

There are two major reasons for rising rapes against children over the past four years: First, a rise in reporting; and second, new criminal laws, experts told IndiaSpend.

“Reporting of child abuse and rape cases have increased due to the lowering of the stigma attached, but incidence has also increased, definitely,” said Amit Sen, a child and adolescent psychiatrist from Delhi.

The rise of social media has created awareness about child abuse, said Sonali Gupta, a clinical psychologist from Mumbai. “Furthermore, many instances of celebrities opening up about being abused in their childhood (for instance, the actor Kalki Koechin) have also motivated many parents to report abuse,” she said.

Simultaneously, the introduction of POCSO in 2012 and the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act in 2013 was instrumental in higher reporting of rape against children—although sexually active teenagers now run the risk of consensual intercourse being classified as rape.

The new definitions of rape

“The definition of rape… now includes many more sexual actions than were earlier classified as sexual assault,” said Ved Kumari, a professor at Delhi University's Faculty of Law. She explained how POSCO has raised the age of consent for girls from 16 to 18 years. This means boys who have consensual sex can be charged with rape.

Before the new laws, only “peno-vaginal assault” was considered rape with an excessive emphasis on torn hymens (which continues), according to Shaibya Saldanha, co-founder of Bangalore's Enfold Trust, an advocacy that focuses on child sexual abuse.

“But now, injuries to vagina and other parts are considered as evidence,” said Saldanha. “For boys, it was even more difficult as only serious anal injuries would be considered as evidence. POCSO states that a child's testimony and circumstantial evidence will be of paramount importance.”

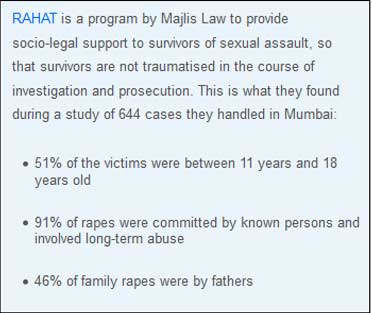

As a consequence, there has been “a huge increase” in child-sexual-abuse cases after the POSCO Act of 2012, said Audrey D'Mello, Project Director at Mumbai's Majlis Law, a legal advocacy.

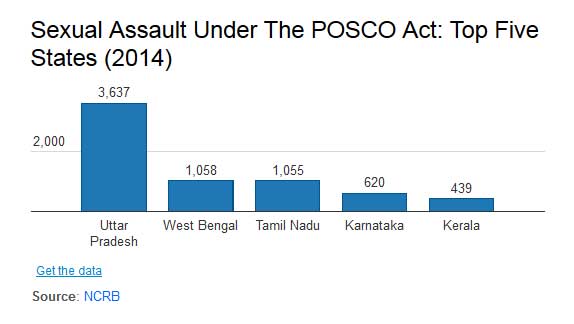

UP tops the list in POCSO cases, accounting for 40% of the total cases, followed by West Bengal and Tamil Nadu.

However, little has changed in rural areas, which are largely untouched by media pressure, political interest and the NGOs who help in registering cases.

“In rural areas, police are extremely reluctant to file a FIR,” said Rakesh Senger, Project Director–Campaigns and Victim Assistance, Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), or Save Childhood Movement, an NGO. “Only extreme cases such as a gang rape or a multiple rapes by a single person are accorded some importance.”

Most abuse is by people close or known to children

It is known that about nine of 10 rapes and sexual assaults are carried out by people known to the victim. That holds true in the case of children as well.

As many as 86% of all rapes in 2014 were committed by a person known to the victim, according to the NCRB.

“We all talk about installing CCTVs and making public spaces, but children are being abused more by known people including family members, therefore, the discourse needs to focus in the right direction,” said D'Mello of Majlis Law.

“In most of the cases that come to us… very few cases involve strangers,” said Pooja Taparia, founder of Arpan, an NGO that works with affected children.

Therefore, apart from spending quality time with children, parents and schools need to provide sex education to children and empower them to talk about possible abuse.

“Pedophiles target children who are easily accessible (For e.g. [the pedophile could be] a close relative, watchman, guard or school conductor),” said Aarti Rajaratnam, a psychologist from Chennai. “Children who are emotionally vulnerable and needy, whose parents are out for long hours and do not spend quality time with them are most likely to be swayed by pedophiles.”

Police, judiciary and hospitals lack sensitivity in dealing with abused children

“Show me the undergarment you were wearing before being raped.” This was the demand that a policeman made of a 12-year-old girl in a Jashpur (Chhattisgarh) police station in June this year.

The case was narrated by the BBA's Senger, who has worked with police of several states. He said police frequently threaten or intimidate child victims of sexual abuse, pressuring them to retract statements; in some cases, they try to broker a “compromise” between rapist and victim.

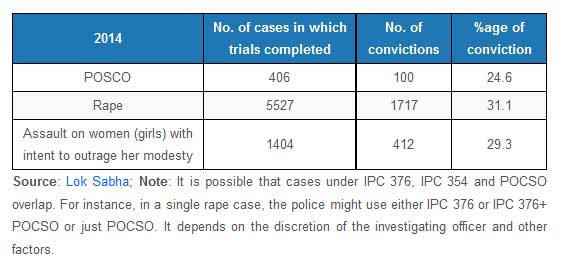

The conviction rates for rape cases, cases under POCSO and assault on women (girl child) with intent to “outrage her modesty” under Section 354 IPC in 2014 were 31.1%, 24% and 29.3% respectively (of cases whose trials have been completed), according to the NCRB.

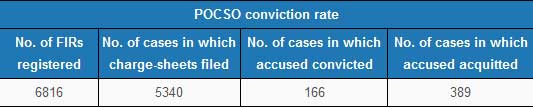

Data tabled in the parliament reveal 6,816 FIRs (till October 2014) filed under the POCSO Act, with 166 convictions, a rate of no more than 2.4%.

The data might be unclear, but those who deal with abused children make it clear that insensitivity and the unhelpful attitude of police, lawyers and untrained hospital staff makes prosecution and conviction difficult.

“There is absolutely no sensitivity amongst policemen to handle cases of child abuse. POCSO as a law is quite good but it needs to be implemented effectively as well,” said Sen, the Delhi psychiatrist.

In several court trials, said Chennai's Rajaratnam, she has witnessed defence lawyers making the process so “unpleasant and humiliating for the children that their trauma increases”. Often, parents decide it is better to drop out of the case than traumatise a child further.

D'Mello of Majlis Law believes the only way forward is to work within the system. She explained how Majlis, for years, has provided the Mumbai police training and sensitisation, created standard operating procedures to handle sexual-assault cases, made officers aware of POCSO Act provisions, and helped when they recorded victims' statements.

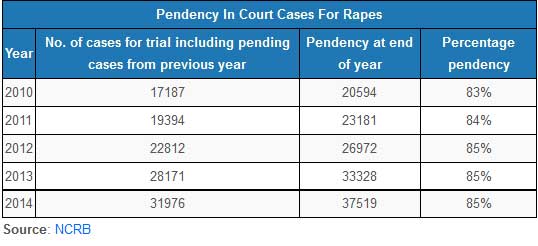

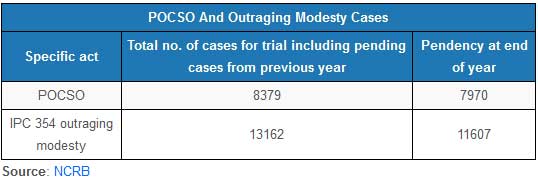

It is clear there is much to do. In 2014, 85% of child-rape cases—registered over five years—were pending, as were 95% of POCSO cases and 88% of cases for “outraging modesty”, according to the NCRB.

Bringing support systems together—the lesson from Bangalore

It's not just the police and the justice system, hospitals too are not equipped to handle sexual-abuse cases against children. The issues include a lack of privacy for victims and trained staff.

“Another problem is that every stakeholder likes to blame the other stakeholder,” said the Enfold Trust's Saldanha. “Police blame the hospital. Hospital blames the police and so on,” she said. “Therefore, it is important to bring all stakeholders together, which is why we started Collaborative Child Response Units (CCRU).”

In 2011, Enfold helped set up CCRUs in hospitals, the first such units in India—aimed at providing child victims with proper treatment and social and legal support. A collaboration between Enfold, the government of Karnataka and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), there are now CCRUs in three leading Bangalore hospitals.

These centres also link and train counsellors, medical practitioners, social workers, the judiciary, legal workers, NGOs and the police—with the well-being of the abused child in mind.

Hospitals are clearly a vital link in the chain. “It is necessary to train doctors to handle sexual assault cases as well as document case details,” said Shailesh Mohite, Head, Forensic Department at Nair Hospital, Mumbai. “Since their testimony matters a lot, they must be trained to handle cross examination at court.”

Social media can endanger children

The exploding growth of social media has increased awareness about child-abuse issues, but it is also endangering the safety of children.

Experts said that exposure to the Internet occurs earlier than ever, and it is important that parents are careful about sharing pictures and details of their children online.

Recently, a series of stories on The News Minute, a new portal, explored how online pictures on Facebook were being used by pedophiles.

“This should be a wake-up call for all of us as parents,” said Vidya Reddy of Chennai-based NGO, Tulir-Centre for the Prevention and Healing of Child Sexual Abuse. “There are people interested in our children sexually. Social media are only a reflection of society.”

Shakthi V, a popular blogger and writer, has written a post on how parents should guide their children in accessing the internet.

“I know children who fake their age to get on Facebook, there are some who create profiles on all social sites faking their ages,” he writes. “This is just one group of kids. There are others who get on to dating sites and get into all sorts of messy things there. The overall conclusion is that kids and the internet are a potent combination that goes very bad.”

(Indiaspend.org is a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit)