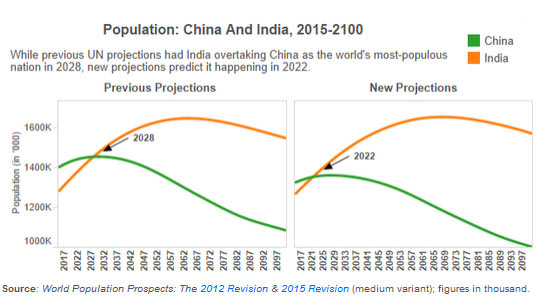

India will overtake China as the world's most populous nation by 2022, says a new UN report which revises its previous estimates, which put the date around 2028. In 2015, India had 1.311 billion people, according to the UN's new estimates, against China's 1.376 billion, a difference of 65 million people. India was earlier estimated to reach 1.35 billion by 2020, against China's 1.43 billion. Only by 2028 was India estimated to have 1.454 billion, against 1.453 billion in China.

The UN's World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision builds on previous data by incorporating additional results from the 2010 survey of national population censuses, as well as findings from recent specialised demographic and health surveys from around the world. It provides the demographic data and indicators to assess population trends at the global, regional and national levels and to calculate many other key indicators commonly used by the UN system. If the new projections hold good, India will also be–or continue to be–far more densely populated than China. India's population density is already more than double that of China's, which has 141 people per sq km against India's 382 people per sq km.

How the date moved from 2050 to 2022

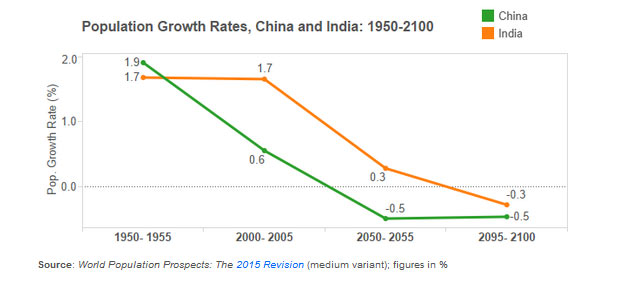

India's population ascendancy was first estimated to take place in 2050, then gradually lowered to 2040 and then 2030, said Prof Siva Raju, Chair of the Centre for Population, Health and Development at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. But the UN's projections have changed, with China's population growth rate decelerating much faster than India's, which explains why India will top the world's list in 2022.

The two giants, China and India, now have 19% and 18%, respectively, of the world's population, states the UN report released on July 29. Five Asian countries–China, India, Indonesia Bangladesh and Pakistan–are among the 10 largest countries in the world. Two are in Latin America (Brazil and Mexico), one each in Africa (Nigeria), in Northern America (USA), and Europe (Russian Federation). The world now has 7.3 billion people. This is expected to rise to 8.5 billion by 2030, 9.7 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100.

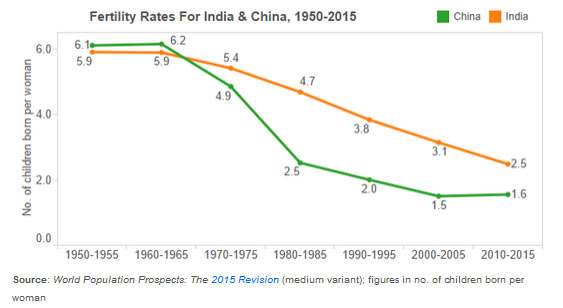

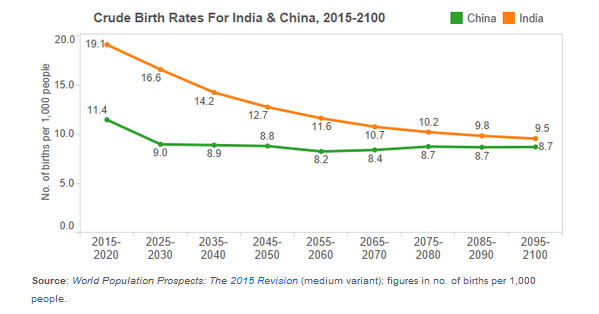

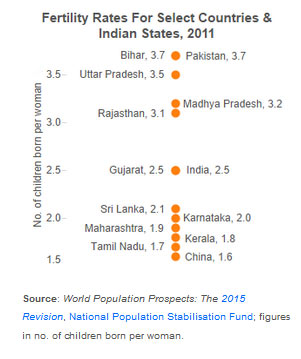

The report reveals that between 2015 and 2050, half the world's population growth is expected to be concentrated in nine countries: India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, the US, Indonesia and Uganda. Previously, India was expected to surpass China by 2035, Dr Fauzdar Ram, Director of the International Institute for Population Sciences in Mumbai told IndiaSpend. China's fertility rates–the average number of children a woman can be expected to bear during her lifetime–has dropped much lower than India's, which is why its population is growing less than India's.

Based on the UN's latest assessment, the total fertility rate in China was estimated at 1.55 children per woman in 2010-2015, while that of India was estimated at 2.48, slightly under the world average, François Pelletier, Chief, Population Estimates and Projections Section, UN Population Division in New York, told IndiaSpend. Overall, India had seen an appreciable decline in its fertility over the years–the fertility rate has fallen to 2.48 from 5.9 in 1951–though that process was faster in China, which had a fertility rate of 6.11 in 1951.

India's higher fertility contributed to the higher population growth. Lastly, the population growth of China in recent years was mainly due to “population momentum” (the population's total fertility has fallen below the replacement level since the early 1990s) and this will also contribute to the population growth in India for the coming decades.

Over the last decade, from 2001-2011, India's population grew at only 1.64% per year, as against 1.96% in the previous decade. However, since the base was so large, the population increase was “significant”, amounting to around 18 million per decade or 2 million per year, Dr Ram said.

Government's estimates overwhelmed–or are they?

In May, Union Health Minister J P Nadda told the Rajya Sabha that India's population would cross China's by 2028. He cited the UN's 2012 Revision. However, he defended the government's population control measures, which lowered the decadal growth rate from 21.54% for 1991-2000 to 17.64% during 2001-11. Nadda cited the Sample Registration System to demonstrate how the total fertility rate also declined from 3.6 in 1991 to 2.3 in 2013.

As many as 24 states and union territories had achieved the replacement total fertility rate of 2.1 or less, which ensures zero population growth. Some experts believe that the UN's revised estimates are just projections, which may or may not materialise.

India's population will certainly overtake that of China's, but the exact year could vary. The revised estimates are a revision based on actual growth, which is different from the growth projected earlier, according to Sona Sharma, Joint Director, Advocacy & Communications of the Population Foundation of India, a Delhi-based non-governmental research group.

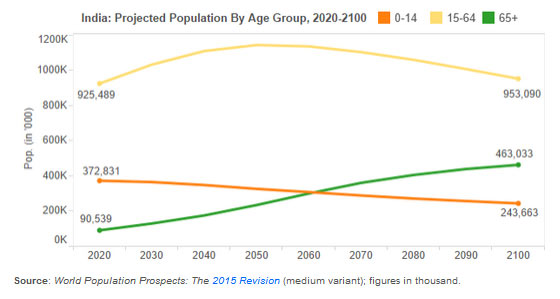

India wasn't growing faster than imagined; its decadal growth rate had declined, she observed. India's bulge was also due to its huge population of young people in the reproductive age, which contributed to its population momentum. All the additional 3.7 billion people from now to 2100 will enlarge the population of developing countries, which is projected to rise from 5.9 billion in 2013 to 8.2 billion in 2050 and to 9.6 billion in 2100, the UN report said. It will mainly be distributed among the population aged 15-59 (1.6 billion) and 60 or over (1.99 billion), as the number of children under age 15 in developing countries will hardly increase.

China's was a hugely mixed story, Sharma believed. It had developed at the grassroots since the 1970s by investing in education and health, unlike India. Its fertility rates began to decline even before the imposition of the one-child policy. Most in India would find this policy undemocratic in that it deprives a family of taking its own decisions about having more than one child.

However, India's family planning programme–one of the first and biggest in the world, when launched in the 1950s–suffered a setback during the forced sterilisation of women and men during the national emergency between 1975 and 1977, the 40th anniversary of which was observed last month.

The real lesson lies in social progress–Kerala shows the way

The real lesson of the discrepancy between China and India lay in the former's better social progress indicators across all fronts, as the UN Development Programme's Human Development Reports indicate year after year, said Sharma.

Kerala and Sri Lanka have proved exceptions in that they reached the replacement level of 2.1 (children born to a woman) even before China. All the southern states, except Karnataka, are on the same path, as IndiaSpend previously reported.

As we can see, the population in the southern states is stablising, even falling below replacement levels. It is the northern states, primarily, with their still-high fertility rates–although these have dropped–that continue to boost India's population.

The world's population projections are important because they have been released at a time when the UN's Millennium Goals, the deadline for which was this year, are being replaced this year by the much more ambitious Sustainable Development Goals, all of which are measured by the population reached.