India spends only 1.3% of its GDP on healthcare and faces a healthcare crisis, especially in rural areas. This crisis is likely to be aggravated due to a reduction in the healthcare budget, as IndiaSpend reported.

“In all the farm households I've visited, where people have killed themselves, the single largest component of family debt was health costs,” said Sainath, the journalist.

The IB report does not acknowledge healthcare at all. It blames “rising farmer suicides on an erratic monsoon (at the onset stage), outstanding loans, rising debt, low crop yield, poor procurement rate of crops and successive crop failure (sic)”.

Do loan waivers, compensation for crop-losses and other aid help farmers?

Loan waivers are not relevant to farmers who borrow from private moneylenders. This was a view echoed by all the researchers IndiaSpend spoke to, as well as the IB report.

The larger issue is declining farm livelihoods. “The development discourse and public policy have to move out from piecemeal approaches that get reduced to income or yield,” said IGIDR's Mishra. “They have to have a livelihood and quality-of-life focus.”

“Despite state-specific differences, a common thread running across the story of suicides is the adverse implications on the livelihoods and the quality of life of farmers and their families,” he said.

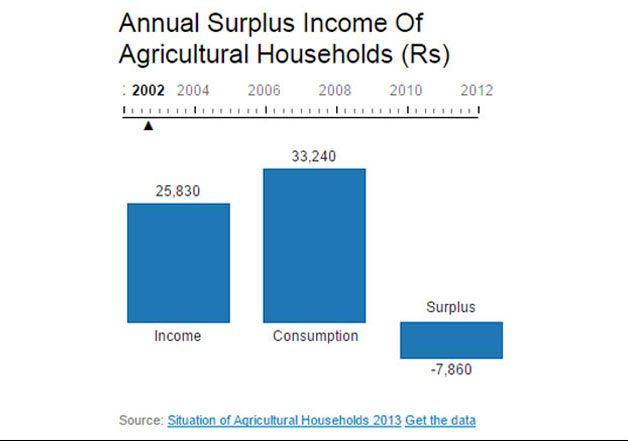

The new NSSO data substantiate his point. The average surplus income (income minus consumption) of an agricultural household was Rs 2,436 per annum (Rs 203 per month) in 2012-13, which means that a farmer rarely has savings.

The government's policy of waiving debts is reactionary and cannot substitute for long-term policy, concluded a recent research brief by Shamika Ravi, Fellow, Brookings Institution India.

With livelihoods so imperiled, suicides are likely to grow. But aside from the reasons we have listed, there is another complicating factor: Media reportage of suicides.