On the heels of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Independence Day “Start-up India, Stand up India” campaign launch, finance minister Arun Jaitley introduced the India Aspiration Fund, a Rs 2,000 crore ($304 million) seed fund for start-ups.

This is small change compared to the Rs 33,125 crore ($5 billion) invested in start-ups in 2014 and Rs 23,187 crore ($3.5 billion) in the first half of 2015.

Nevertheless, it shows that start-ups are on the radar of the government—and that's a good thing because young companies are effective job creators, far more effective, it emerges, than micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), India's long-time strategy for employment generation and income redistribution:

ALSO READ: MSMEs to play lead role in 'Make in India': Kalraj Mishra

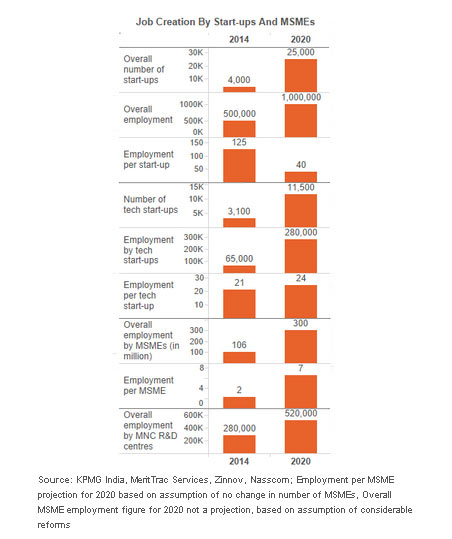

- Today, 46 million MSMEs employ 106 million people at an average of 2.3 people per enterprise, according to this 2015 KPMG report. In 2010, over one-third of enterprises in the informal sector enterprises were one-person establishments.

- In 2014, India's 4,000-odd documented start-ups (not counting thousands outside the monitored ecosystem) employed 500,000 people at an average of 125 per enterprise, according to Premjith Alampilly of MeritTrac Services, an assessment company that monitors the start-up ecosystem.

- Roughly 3,100 tech start-ups employed 65,000 people last year, at an average of 21 per enterprise, according to Zinnov, a consultancy, and Nasscom, a software industry association. That is as much as 23% of the workforce currently employed by multinational R&D centres in India. By 2020, the workforce of 11,500 tech start-ups will be more than half the size of multinational R&D centres.

India badly needs to create more jobs.

One million Indians join the labour force every month, and will continue to do so over the next two decades. But India created only 420,000 new jobs across eight core industries in 2014, and 410,000 jobs the previous year.

The net result: India's official employment rate was 4.9% in 2013, which means 44.79 million unemployed people. Starting-up en masse might help avert the predicted increase in the official employment rate to 7% by 2030.

Young companies, large companies are job creators, small firms aren't.

Small- and medium-scale firms have enjoyed special incentives in India. Starting in 1967, certain sectors of manufacturing were reserved for the small-scale sector. The aim was to promote industry, create jobs and redistribute wealth.

On the face of it, the MSME sector has done well. It employs 28% of the country's workforce, contributes 8% of India's gross domestic product, 45% of the nation's industrial output and 40% of exports.

As good as that sounds, it isn't something to cheer about, argue experts.

Promoting small industry through reservations has cost India many jobs, according to a 2014 study by Wharton multinational management professor Ann Harrison and others.

To understand if small industry in India really is an engine of growth and jobs creation, Harrison studied the impact of de-reservation of select items for small-scale industry on employment nationwide.

“We found that districts that were more exposed to the de-reservation policy experienced a 7% increase in overall employment between 2000 and 2007,” Harrison told IndiaSpend.

De-reservation decreased employment among smaller, older establishments but increased overall employment by encouraging the growth of younger (and larger) establishments—those that are most likely to pay higher wages, create more investment, be more productive, and generate growth in employment.

“Young firms (and large companies) generate far more jobs than small ones do,” said Harrison.

Essentially, she found that small firms stay small.

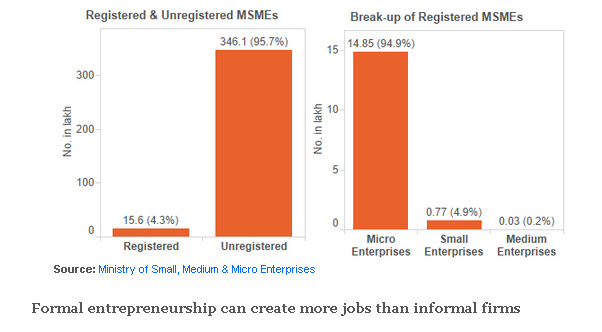

Statistics support that finding. Micro enterprises account for 94.9% of enterprises in India, according to the Fourth All India Census of MSMEs. Small enterprises make up 4.9% while medium enterprises constitute a miniscule 0.2% of the pie.

Formal entrepreneurship can create more jobs than informal firms

If new firms create jobs, would it help to promote any sort of entrepreneurship, including more MSMEs?

World Bank economist Ejaz Ghani supports any kind of entrepreneurship, informal or formal.

Who creates jobs? a 2011 India-specific study he co-authored, contends that India has too few entrepreneurs for its stage of development.

One-person new firms can provide better opportunities than unemployment or employment in subsistence agriculture, Ghani told IndiaSpend. “One-person new firms can also enable transitions to urban sectors,” he said.

The snag: One-person new firms employ only the entrepreneur. They don't create jobs for society.

At the outer limit, registered MSMEs employ 5.95 people per unit. But less than 5% of all MSMEs are registered. The vast majority are unregistered, employing 2.06 people per unit.

India's current crop of start-ups is mostly incorporated, with the vision to access capital markets and scale, employing more people in the process.

Many start-ups—especially e-commerce ventures and those in the digital space—are growing faster than ever because of the growing numbers of Indians transacting online.

ALSO READ: CII backs govt's Rs 40k-cr tax demand from FIIs

“Traction that used to take 12 months is now happening in 12 weeks,” said Anand Daniel, a venture investor from Accel Partners in this news report.

It's not only about creating jobs, but also about innovating

A key takeaway from Harrison's study is that young firms are really the key innovators in India.

“India's new crop of start-ups is big on innovation,” observed Preeti Anand, associate director at Zinnov, the consultancy. “These new generation companies are driving product, process and business model innovations at a fast pace, as a result, fundamentally transforming businesses across multiple verticals.”

In contrast, innovation is a vital missing ingredient in most existing MSMEs.

Harrison's research tells us that instead of innovating, small enterprises struggle to survive when the economic protection they are accorded is taken away. Only 2.6% of MSMEs had carried out any sort of innovation, according to a 2012 Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) and commerce ministry survey.

Innovation helps enterprises grow, but the right talent is a key enabler.

Well-funded technology start-ups (funding in excess of $10 million) can better afford engineering graduates than can MSMEs. Many start-ups pay salaries that match those paid by multinationals to their R&D workforce. Start-ups may also offer equity and stock options.

Most start-ups make good employers

In 2014, Alampilly of MeritTrac Services estimated that India's 4,000 odd start-ups hired around 50,000 people.

Alampilly's estimates were based on the documented pool of start-ups being incubated or supported by government-established incubators and accelerators, industry bodies like Nasscom, Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), and academic institutions, such as the IITs.

Among those hired by start-ups are the best brains from premier technology institutions and management schools, he said.

Start-ups are way ahead of MSMEs, some say even ahead of large companies, in offering employees opportunities to develop skills and acquire new ones. To attract and retain talent, some offer better than industry average pay and frequent pay raises.

In October 2010, when Dushyant Sinha floated Integrated Centre for Consultancy Pvt. Ltd., a media and communications company, it was a one-man show. Today, he employs 60 people across five offices.

“Our entry-level employees earn double of industry standards,” said Sinha. “I myself earn three times what I would have earned as an employee.”

At Lybrate, an online healthcare communication and delivery platform for doctors, employee salaries are at par with the best in the industry. “We offer bi-annual salary reviews, flexible working hours and a work from anywhere policy,” said Lybrate CEO Saurabh Arora.

Start-ups employ and help the self-employed

A certain kind of start-up, called aggregators, is positively impacting the prospects of self- employed, semi-skilled and skilled professionals.

Aggregators help providers to get word out about their services and grow their business, said Anil Nair, founder of GenieJi, an aggregator of service providers in Pune.

GenieJi employs no more than 20 people. Its associate service providers, however, hire professionals in events management, home maintenance, finance, packers and movers, construction, numbered more than 1,000 at the last count.

And GenieJi is one of many start-ups in the home services sector—TaskBob, Timesaverz, Servesy, Zimmber, DoorMint, UrbanClap, WorkHorse, Housejoy and others—all of whom aggregate the services of thousands of providers.

Lybrate helps people find and communicate with trusted doctors online.

In two years, Lybrate has grown from just two people to 50 employees. Beyond this team, Lybrate aggregates the services of more than 80,000 doctors.

“On the one hand, Lybrate helps doctors expand the geographic contours of their practice and monetise their unpaid/spare time,” said Arora. “On the other, it gives people across India online access to specialists.”

(Indiaspend.org is a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit)