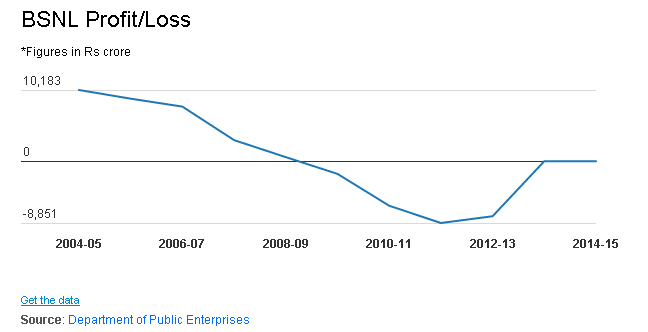

New Delhi: Once India's leading telecommunication giant and among its most-profitable state-run companies, Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL) has posted a loss for the fifth straight financial year.

BSNL lost Rs 3,785 crore during 2014-15, according to provisional data released by the government. The accumulated loss of BSNL has now swelled to about Rs 36,000 crore ($6 billion), with the company making losses since 2009-10.

As the first part of this series explained, BSNL accounts for 35% of the Rs 20,000-crore loss shown by 71 PSUs in 2013-14. If BSNL's losses can be stemmed, the Indian government will have more money to spend.

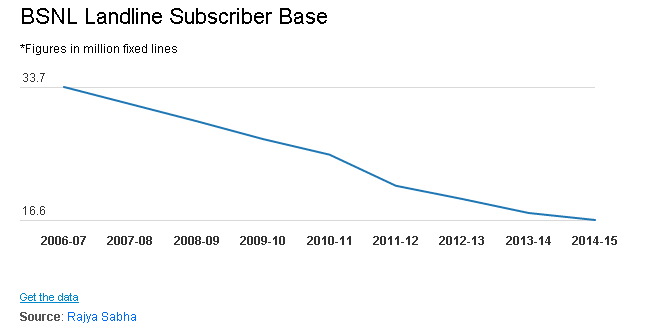

BSNL's fortunes declined dramatically because its subscribers moved from landlines to mobile phones (as IndiaSpend reported earlier), and it spent increasing sums of money on salaries for its 2.38 lakh employees, Minister of Communications and Information Technology Ravi Shankar Prasad told Parliament in December 2014.

However, a closer look at the data and events in the telecom industry over the last decade reveals how government policies killed its golden goose. The decline in revenue was not foregone but a result of the government's gradual whittling of promised subsidies, while keeping the company's “social obligations” intact.

Those obligations included expanding a rural landline network that recovered barely a tenth of its costs, compulsory purchase of 3G spectrum–or telecom bandwidth–and bureaucratic delays in buying equipment.

ALSO READ: Government blames UPA rule for poor financial condition of BSNL

Despite repeated reminders over 10 days, BSNL did not respond to IndiaSpend‘s questions, emailed to Chairman and Managing Director Anupam Shrivastava.

Let's examine four reasons that led to BSNL's decline:

1) Rural landline networks: Big push at big loss

After 2002, as the mobile-phone revolution spread, BSNL's landline subscriber-base fell from 33.7 million in 2006-07 to 16 million in 2014-15, according to telecom ministry data compiled from the Parliament website.

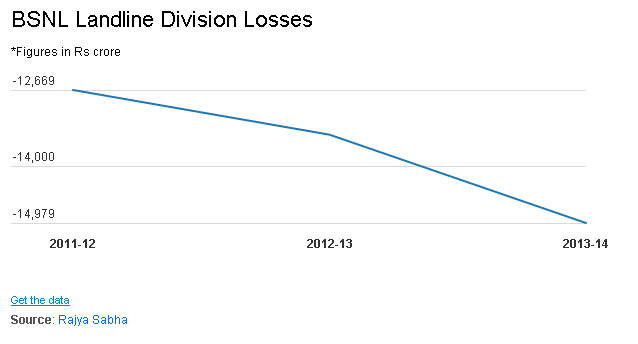

In 2013-14, the landline division posted a loss of Rs 14,979 crore.

The government says subscribers giving up landlines was a major blow, and it was, but the expansion of a rural network that was already making losses was equally responsible.

On an average, BSNL was spending Rs 702 per line per month on rural landline services against a revenue of about Rs 78 per line per month, according to the 2008-09 audited accounts of BSNL.

BSNL was tasked with building, expanding and running the rural network at minimal tariffs as part of its social obligation, said P Abhimanyu, General Secretary of BSNL employees union. In 2003-04, the PSU reported a loss of about Rs 9,528 crore in the rural landline segment.

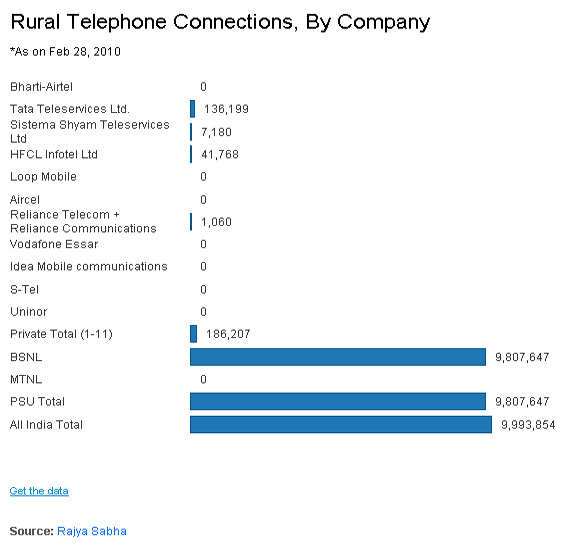

Of 593,601 inhabited villages in the country, according to Census 2001, BSNL had installed public telephones in 586, 000 of them by December 2014.

Since returns are low, private telecom operators ignore village landline networks, providing no more than 2% of connections in 2010.

2) Withdrawal of subsidies after being pushed into “social obligations”

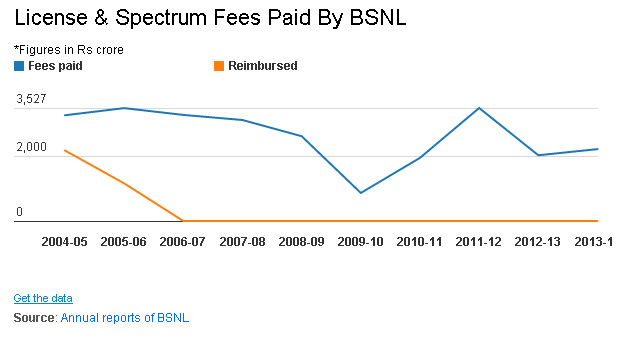

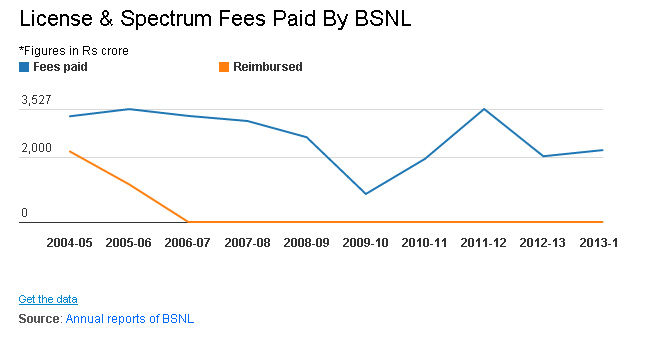

In view of the “immense rural and social obligations,” as the telecom policy of 1999 described it, the government promised to exempt BSNL from license fees and spectrum charges. The government reneged on that promise in 2006-07, according to this Economic Times report.

Between 2001-02 and 2003-04, BSNL was reimbursed licence fees and spectrum charges. That fell to 2/3rd and 1/3rd, before ending in 2006-07.

BSNL lost Rs 3000 crore every year since. More was to follow.

To fund rural landline services, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), in January 2003, imposed an “access deficit charges” (ADC) on all operators to fund subsidies for existing rural telephones.

In 2003-04, the ADC subsidy was estimated at Rs 13,000 crore annually, most (around Rs 10,800 crore) for BSNL, which operated 95 per cent of India's rural telephones. That year, TRAI reduced this amount to Rs 5,200 crore, paring it further to Rs 3,000 crore in 2006-07 and to Rs 2,000 crore in 2007-08.

Eventually, the government scrapped the subsidy in 2008, arguing that BSNL received financial assistance in various forms.

The ADC was temporary because it would not have been fair to ask private companies to fund it, said Mahesh Uppal, a Delhi-based telecom consultant. Instead, the government promised Rs 2,000 crore every year from the Universal Service Obligation (USO) fund, created by imposing a levy of 5% on the revenue all telecom operators. It did not last: Rs 1,250 crore from the USO fund for 2012-13 to BSNL is still pending.

BSNL had invested about Rs 25,000 crore in its rural network and before it could recover this money, the ADC was “arbitrarily withdrawn,” said GL Jogi, a senior official with BSNL and General Secretary of Sanchar Nigam Executive Association.

Against a loss of almost Rs 10,000 crore a year to meet social obligations, the government paid no more than Rs 1,500 crore to BSNL from in 2011-12.

3) Compulsory purchase of 3G spectrum at government-mandated prices

In 2010, when private telecom companies purchased spectrum, they bid only for areas–or circles, in official parlance–that were expected to turn profits.

BSNL had no such choice.

The then telecom minister Kapil Sibal said BSNL was obliged to purchase pan-India broadband wireless access and 3G (third-generation) spectrum (excluding Delhi and Mumbai) for Rs 8,318 crore and Rs 10,187 crore respectively, according to this Business Standard report.

ALSO READ: BSNL to offer minimum broadband speed of 2 Mbps from 1 October

“BSNL was allocated infeasible and cost-intensive spectrum in the higher-frequency range (2.6GHz) against lower-frequency radio waves (2.3GHz) given to private players,” said Abhimanyu, a senior employee with BSNL. “Lower frequency means better services and less capital expense on infrastructure.”

The government has finally accepted concerns raised by BSNL and in September 2013 it agreed to refund broadband wireless access and spectrum money, according to this report in the Hindu.

Since BSNL was not allowed to bid, it was unfair to make the company buy expensive assets it could not use, said Uppal.

BSNL paid Rs 18,000 crore for broadband wireless access and 3G spectrum in 2010, while Bharti, Vodafone, Aircel and other operators paid between Rs 2,000 and 6,000 crore, reported The Economic Times.

That Rs 18,000 crore decimated BSNL's cash reserves, from Rs 29,300 crore to Rs 1,700 crore, according to data presented in Parliament.

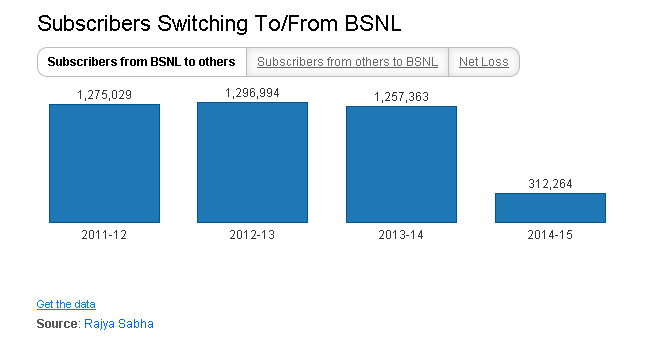

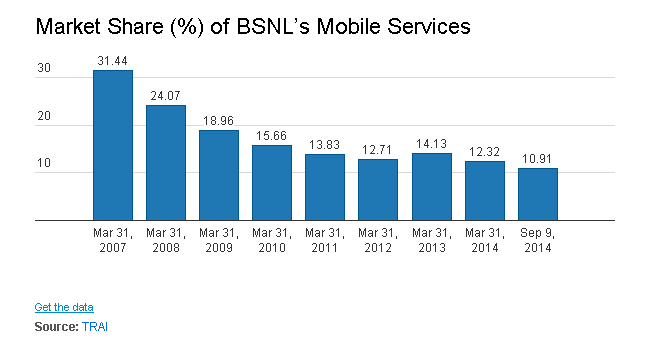

With low cash reserves and growing financial distress, BSNL's operations faltered, and nearly 800,000 mobile subscribers switched to other operators; its market share declined from 16% to 10%.

4) How the government fiddled with tenders and orders

When BSNL's fortunes were at a peak in 2006, its expansion plans were delayed by interference from the United Progressive Alliance government.

In 2006, a tender for 45.5 million mobile lines was delayed for more than six months; eventually, after a year, then telecom minister A Raja (arrested in February 2011 for the 2G Spectrum Scam), reduced the tender size to 14 million, according to this report.

Two years later, in 2008, another tender of 93.3 million mobile lines ran into controversy after Nokia Siemens got disqualified on technical grounds leaving only Ericsson in the fray, and it was cancelled in March 2010. Between 2005 and 2008, BSNL's market share dropped from 38% to 25% after a delay in equipment purchases.

Does India really need BSNL?

India really does need BSNL, its employees argue.

BSNL forces private operators to reduce their prices, said Rakesh Sethi, General Secretary of All India BSNL officers' association. “From free incoming calls, one-rupee one-India plan to the recently launched free-roaming scheme, BSNL has been leading the market,” said Sethi.

BSNL is also important to ensure e-governance projects reach rural India. “It is only BSNL that has reached most of the villages and continues to expand its network in rural areas,” said Jogi.

Most private companies have not taken mobile services to rural areas (each company is supposed to serve 21,600 tower sites in villages), Business Line reported.

BSNL also works in strategically important but likely unprofitable national projects, such as the National Optic Fibre Network, Network for Spectrum for defence and the Left Wing Extremist for areas dominated by India's Maoist insurgency.

Should BSNL be privatised? “Instead of privatising it,” said Uppal, the telecom consultant, “the government should look for a strategic partnership with any private organisation with a proven track record.”

(Indiaspend.org is a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit)