Scientists coin new approach to aid quest of elusive dark matter

Over the past three decades, the search for dark matter has focussed mostly on a class of particle candidates known as weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs).

Combining astronomical surveys and gravitational wave observations may give a major boost to the search for the elusive dark matter, scientists say. Since the 1970s, astronomers and physicists have been gathering evidence for the presence in the universe of dark matter: a mysterious substance that manifests itself through its gravitational pull.

However, despite much effort, none of the new particles proposed to explain dark matter have been discovered, said researchers from the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

In the study published in the journal Nature, researchers argue that the time has come to broaden and diversify the experimental effort in the quest for the nature of dark matter.

Over the past three decades, the search for dark matter has focussed mostly on a class of particle candidates known as weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs).

WIMPs appeared for a long time as a perfect dark matter candidate as they would be produced in the right amount in the early universe to explain dark matter, researchers said.

They might also alleviate some of the most fundamental problems in the physics of elementary particles, such as the large discrepancy between the energy scale of weak interactions and that of gravitational interactions, they said.

While such a natural solution sounds like a very good idea, none of the many experimental strategies performed to search for WIMPs has found convincing evidence for their existence.

Researchers, including those from the University of California, Irvine in the US, argue that it is time to enter a new era in the quest for dark matter -- an era in which physicists broaden and diversify the experimental effort, leaving as they say "no stone left unturned".

"What makes the current time ripe for such a widened search is that several search methods for such a wider search already exist or are in the process of being completed," said Gianfranco Bertone from the University of Amsterdam.

Researchers point towards astronomical surveys, where tiny effects in the shapes of galaxies, of the dark matter halos around them, and of the gravitationally bent light coming around them, can be observed to learn more about the potential nature of dark matter.

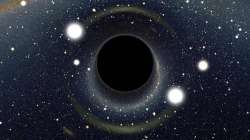

They noted the new method of observing gravitational waves, successfully carried out for the first time in 2016, as a very useful tool to study black holes -- either as dark matter candidates themselves, or as objects with a distribution of other dark matter candidates around them.

Combining these modern methods with traditional searches in particle accelerators should give the search for dark matter a major boost in the near future, researchers said.