NASA probe Juno captures volcanic plumes on Jupiter's moon Io

On December 21, during winter solstice, four of Juno's cameras captured images of the Jovian moon Io, the most volcanic body in our solar system.

Data collected by NASA’s Juno spacecraft during recent flyby point to a new heat source close to the south pole of Jupiter's moon Io that could indicate a previously undiscovered volcano.

On December 21, during winter solstice, four of Juno's cameras captured images of the Jovian moon Io, the most volcanic body in our solar system.

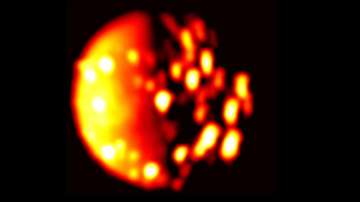

JunoCam, the Stellar Reference Unit (SRU), the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) and the Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVS) observed Io for over an hour, providing a glimpse of the moon's polar regions as well as evidence of an active eruption.

"We knew we were breaking new ground with a multi-spectral campaign to view Io's polar region, but no one expected we would get so lucky as to see an active volcanic plume shooting material off the moon's surface," said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of the Juno mission.

"This is quite a New Year's present showing us that Juno has the ability to clearly see plumes," said Bolton, associate vice president of Southwest Research Institute's Space Science and Engineering Division.

The images show the moon half-illuminated with a bright spot seen just beyond the terminator, the day-night boundary.

"The ground is already in shadow, but the height of the plume allows it to reflect sunlight, much like the way mountaintops or clouds on the Earth continue to be lit after the sun has set," said Candice Hansen-Koharcheck, the JunoCam lead from the Planetary Science Institute.

After Io had passed into the darkness of total eclipse behind Jupiter, sunlight reflecting off nearby moon Europa helped to illuminate Io and its plume. SRU images released by SwRI depict Io softly illuminated by moonlight from Europa.

The brightest feature on Io in the image is thought to be a penetrating radiation signature, a reminder of this satellite's role in feeding Jupiter's radiation belts, while other features show the glow of activity from several volcanoes.

The images can lead to new insights into the gas giant's interactions with its five moons, causing phenomena such as Io's volcanic activity or freezing of the moon's atmosphere during eclipse, added Bolton.

Io's volcanoes were discovered by NASA's Voyager spacecraft in 1979. Io's gravitational interaction with Jupiter drives the moon's volcanoes, which emit umbrella-like plumes of SO2 gas and produce extensive basaltic lava fields.

The recent Io images were captured at the halfway point of the mission, which is scheduled to complete a map of Jupiter in July 2021.

Launched in 2011, Juno arrived at Jupiter in 2016. The spacecraft orbits Jupiter every 53 days, studying its auroras, atmosphere and magnetosphere. Juno has logged nearly 146 million miles (235 million kilometers) since entering Jupiter's orbit on July 4, 2016. Juno's 13th science pass will be on July 16.

The solar-powered Juno features eight scientific instruments designed to study Jupiter's interior structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere.

During its mission of exploration, Juno soars low over the planet's cloud tops -- as close as about 2,100 miles (3,400 kilometers). During these flybys, Juno is probing beneath the obscuring cloud cover of Jupiter and studying its auroras to learn more about the planet's origins, structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere.

JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. The Juno mission is part of the New Frontiers Program managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the Science Mission Directorate. The Italian Space Agency (ASI), contributed two instruments, a Ka-band frequency translator (KaT) and the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM). Lockheed Martin Space, Denver, built the spacecraft. JPL is a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California.

(With inputs from PTI, NASA)