Earth-based telescopes get better at observing exoplanets with low-cost attachment

Scientists have developed a new low-cost technology that allows telescopes on Earth to observe exoplanets with greater precision.

Scientists, including those of Indian origin, have developed a new low-cost technology that allows telescopes on Earth to observe planets beyond our solar system with greater precision. The low-cost attachment to telescopes allows previously unachievable precision in ground-based observations of exoplanets, according to the study published online in the Astrophysical Journal.

With the new attachment, ground-based telescopes can produce measurements of light intensity that rival the highest quality photometric observations from space, the study says.

Researchers created custom “beam-shaping” diffusers – carefully structured micro-optic devices that spread incoming light across an image – that are capable of minimising distortions from the Earth’s atmosphere that can reduce the precision of ground-based observations.

"This inexpensive technology delivers high photometric precision in observations of exoplanets as they transit -- cross in front of -- the bright stars that they orbit," said Gudmundur Stefansson, graduate student at Pennsylvania State University, and lead author of the paper. “This technology is especially relevant considering the impending launch of NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) early in 2018.”

Diffusers are small pieces of glass that can be easily adapted to mount onto a variety of telescopes.

Because of their low cost and adaptability, Stefansson believes that diffuser-assisted photometry will allow astronomers to make the most of the information from TESS, confirming new planet candidates from the ground.

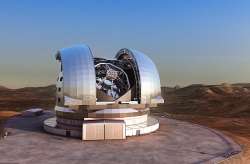

The research team, including Penn State graduate student Shubham Kanodia, tested the new diffuser technology “on-sky” on the Hale telescope at Palomar Observatory in the US, the 0.6m telescope at Davey Lab Observatory at Penn State, and the ARC 3.5m Telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico.

“Beam-shaping diffusers are made using a precise nanofabrication process, where a carefully designed surface pattern is precisely written on a plastic polymer on a glass surface or directly etched on the glass itself,” said Suvrath Mahadevan, associate professor at Penn State.

“The pattern consists of precise micro-scale structures, engineered to mold the varying light input from stars into a predefined broad and stable output shape spread over many pixels on the telescope camera,” said Mahadevan.

In all cases, images produced with a diffuser were consistently more stable than those using conventional methods – they maintained a relatively consistent size, shape, and intensity, which is integral in achieving highly precise measurements.

Using a focused telescope without a diffuser produced images that fluctuate in size and intensity.

A common method of "defocusing" the telescope -- deliberately taking the image out of focus to spread out light -- yielded higher photometric precision than focused observations, but still created images that fluctuated in size and intensity, the researchers found.

By shaping the output of light, the diffuser allows astronomers to overcome noise created by the Earth’s atmosphere. “This technology works over a wide range of wavelengths, from the optical – visible by humans – to the near infrared,” said Jason Wright, associate professor at Penn State.