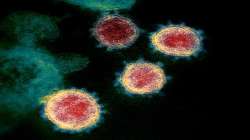

Lab-made 'mild virus' mimics coronavirus, can aid drug, vaccine discovery: Study

Scientists have genetically modified a "mild virus" which generates antibodies in humans just like the novel coronavirus, but without causing severe disease, an advance which they say will enable more labs across the world to safely test drugs and vaccine candidates against COVID-19.

Scientists have genetically modified a "mild virus" which generates antibodies in humans just like the novel coronavirus, but without causing severe disease, an advance which they say will enable more labs across the world to safely test drugs and vaccine candidates against COVID-19. The researchers from the Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis in the US engineered the mildly infecting vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) which virologists widely use in experiments by swapping one of its genes for one from the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

According to the study, published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, the resulting hybrid virus infects cells, and is recognised by antibodies in humans just like SARS-CoV-2, but can be handled under ordinary laboratory safety conditions.

Since the novel coronavirus spreads easily via aerosols, and is potentially deadly, the scientists said it is studied only under high-level biosafety conditions.

They said scientists handling the infectious virus must wear full-body biohazard suits with pressurised respirators, and work inside laboratories with multiple containment levels and specialised ventilation systems.

While necessary to protect laboratory workers, the study note that these safety precautions slow down efforts to find drugs and vaccines for COVID-19 since many scientists lack access to the required biosafety facilities.

"I've never had this many requests for a scientific material in such a short period of time," said study co-senior author Sean Whelan from the Washington University School of Medicine.

"We've distributed the virus to researchers in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Canada and, of course, all over the US," Whelan said.

In order to create a model of SARS-CoV-2 that would be safer to handle, the scientists said they started with VSV, which they added is "fairly innocuous and easy to manipulate genetically. "

VSV, according to the researchers, is a workhorse of virology labs, and primarily a virus of cattle, horses and pigs.

They said it occasionally infects people, causing a mild flu-like illness that lasts three to five days.

The researchers removed the VSV's gene for its surface-protein, which it uses to latch onto and infect cells, and replaced it with the one from SARS-CoV-2, known as the spike (S) protein.

They said this switch created a new virus, dubbed VSV-SARS-CoV-2, that targets cells like the novel coronavirus, but lacks the other genes needed to cause severe disease.

The scientists then used serum from COVID-19 survivors and purified their antibodies, and showed that the hybrid virus was recognised by these antibodies very much like a real SARS-CoV-2 virus that came from a COVID-19 patient.

The study found that antibodies which prevented the hybrid virus from infecting cells also blocked the real SARS-CoV-2 virus from doing so.

It said the patient serum proteins that failed to stop the hybrid virus also failed to deter the real SARS-CoV-2.

The scientists also found that a decoy molecule was equally effective at misdirecting both viruses and in preventing them from infecting cells.

"Humans certainly develop antibodies against other SARS-CoV-2 proteins, but it's the antibodies against spike that seem to be most important for protection," Whelan said.

"So as long as a virus has the spike protein, it looks to the human immune system like SARS-CoV-2, for all intents and purposes," he added.

According to the researchers, the hybrid virus can help scientists across the world evaluate a range of antibody-based preventives and treatments for COVID-19.

They said the new virus could be used to assess whether an experimental vaccine elicits neutralising antibodies, and to measure whether a COVID-19 survivor carries enough neutralising antibodies to donate plasma to COVID-19 patients.

According to the study, the hybrid virus may also help identify antibodies with the potential to be developed into antiviral drugs.

"One of the problems in evaluating neutralizing antibodies is that a lot of these tests require a BSL-3 facility, and most clinical labs and companies don't have BSL-3 facilities," said Michael Diamond, who is also a professor of pathology and immunology at the Washington University School of Medicine.

"With this surrogate virus, you can take serum, plasma or antibodies and do high-throughput analyses at BSL-2 levels, which every lab has, without a risk of getting infected. And we know that it correlates almost perfectly with the data we get from bona fide infectious SARS-CoV-2," Diamond said.

Since the hybrid virus looks like SARS-CoV-2 to the immune system but does not cause severe disease, it is a potential vaccine candidate, he said, adding that the scientists are currently conducting animal studies to evaluate this possibility.