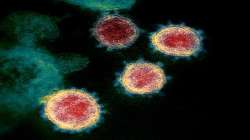

Immune cells involved in protection against COVID-19 identified

Patients suffering from severe respiratory symptoms due to the novel coronavirus infection can rapidly generate an immune response in the form of virus-attacking T cells, suggests a new study which may lead to new vaccine development strategies against COVID-19.

Patients suffering from severe respiratory symptoms due to the novel coronavirus infection can rapidly generate an immune response in the form of virus-attacking T cells, suggests a new study which may lead to new vaccine development strategies against COVID-19. The study, published in the journal Science Immunology, assessed T cells from 10 COVID-19 patients under intensive care treatment.

According to the researchers, including those from the University of California in the US, two out of 10 healthy individuals without prior exposure to the virus also harbored SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells.

Based on this observation, they said these T cells may be cross-reacting to the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, due to past infection with related coronaviruses that cause common cold symptoms.

The findings, according to the researchers, address the poorly understood question of whether SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses vary in patients over time depending on disease severity.

They said the study may help understand whether patients with more severe symptoms can generate protective virus-specific T cells at all, and offer clues regarding the cells responsible for excessive immune responses which has led to the deaths of many COVID-19 patients.

In the research, scientists, including Daniela Weiskopf from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in the US, extracted blood cells from 10 patients at weekly intervals starting soon after they were admitted to the ICU for COVID-19.

They exposed these cells to "megapools" of known SARS-CoV-2 protein components in a technique meant to capture a large fraction of total viral-reactive T cells.

The researchers found that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4+ helper T cells were active in all 10 patients, and CD8+ "killer" T cells were present in 8 out of 10 patients.

They also characterised the cells' production of specific inflammation-triggering cell-cell signalling molecules called cytokines.

According to the scientists, the strongest responses were directed to the virus' spike (S) surface protein, supporting prior work that has pointed to this protein as a promising target to induce virus-specific T cells.

On screening all patients at 0, 7, and 14 days after inclusion in the study revealed that SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells were present relatively early during the course of infection, and increased in these patients over time.

Using the same T cell stimulation technique in age-matched healthy controls, the researchers found SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells in 2 out of the 10 individuals.

They believe a future study of how preexisting SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in healthy controls correlate to protection against COVID-19 can help shed more light on the disease and "and also inform vaccine design and evaluation.