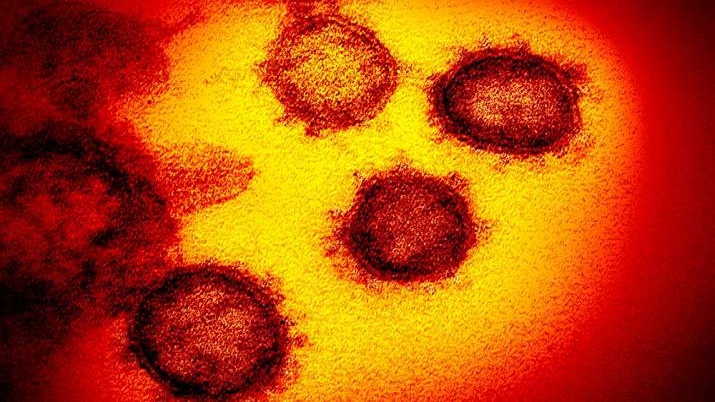

Study sheds light on coronavirus evolution during treatment of chronic infection

Treatment of a COVID-19 patient who had a suppressed immune system with convalescent plasma coincided with the emergence of different variants of the novel coronavirus, says a new case study.

Treatment of a COVID-19 patient who had a suppressed immune system with convalescent plasma coincided with the emergence of different variants of the novel coronavirus, says a new case study. According to the researchers, including Ravindra Gupta from Cambridge University in the UK, the dominant variant that emerged in the patient after the plasma therapy possessed a mutation that is also present in the one first discovered in the UK.

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature, suggest the possibility that evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus can occur in immunosuppressed individuals when prolonged viral replication takes place.

In the study, the scientists assessed a male patient with a compromised immune system in the seventies who was infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

They said the individual was unsuccessfully treated with antibiotics, steroids, and courses of the antiviral drug remdesivir and convalescent plasma therapy over the course of 101 days.

Gupta and his colleagues said they collected samples of the virus on 23 occasions over the course of the treatment.

Their analysis revealed that the infecting variant of the virus possessed the mutation that was first reported in China.

They assigned this variant to the lineage 20B, which had an alteration of an amino acid building block in the 614 molecular position of its spike protein -- the part of the virus which enables it to attach to human cells.

Then the authors found that between days 66 and 82, after administration of the first two rounds of convalescent plasma, a shift in the virus population was observed.

According to the study, a variant with two alterations in the spike protein became prevalent.

One of the changes was a deletion of a building block at the position 69/70 of the spike protein's amino acid molecule chain -- a mutation also present in the UK variant.

The researchers found another mutation that leads to a substitution of a molecule in the 796th position of the protein's amino acid chain.

They said this virus population re-emerged after a third course of remdesivir (day 93) and plasma (day 95).

Commenting on the mutations observed in the study, Simon Clarke, Associate Professor in Cellular Microbiology, University of Reading in the UK, said the virus acquired a mutation to help it escape antibodies, which also had the effect of making it less infectious.

"To compensate for that, another mutation occurred to counterbalance that defect, so the virus maintained its infectiousness," Clarke, who was unrelated to the research, added.

Based on the findings, the authors believe repeated increase in the frequency of this viral population after plasma therapy could mean the observed mutations may be conferring these variants a survival advantage over others.

But scientists believe these variants may not survive when the plasma therapy is stopped.

"..when serum antibody treatment faded over time, the variant decreased in frequency, suggesting that the variant was less fit than the original infecting wild type virus," Jonathan Ball, Professor of Molecular Virology, University of Nottingham in the UK, said in a statement.

"This is important and highlights that the virus will be experiencing lots of different, often opposing, selective pressures, and we need to remember that whenever we consider the potential impact and spread of new variants," Ball, who was also unrelated to the study, added.

The authors concluded that the emergence of this variant was not the primary reason for the failure of the treatment.

Citing the main drawbacks of the research, they said it was only a case study, adding that the generalisability of the conclusions may be limited.

However, Gupta and his colleagues believe the findings warrant caution in the use of convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19 in immunosuppressed patients.

ALSO READ | Scientists decode how coronavirus mutates, escapes antibodies