1,20,000-year-old human footprints discovered in Saudi Arabia | PHOTOS

Researchers in Saudi Arabia have discovered footprints of humans and a number of animals, including elephants, dated to roughly 1,20,000-year-ago.

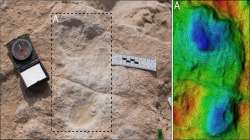

A new study revealed that the landscape of the region now known as Saudi Arabia was completely different in the past from what it looks like today, as researchers have discovered footprints of humans and a number of animals, including elephants, dated to roughly 1,20,000-year-ago. The footprints described in the study published in the journal Science Advances were discovered during a recent survey of the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia.

At an ancient lake deposit dubbed "Alathar" -- meaning "the trace" in Arabic -- by the team, hundreds of human and animal footprints were discovered embedded in the surface, having been exposed following the erosion of overlying sediments.

"We immediately realised the potential of these findings," said one of the study's lead authors Mathew Stewart of Max Planck Institutes for Chemical Ecology (MPI-CE) in Germany.

"Footprints are a unique form of fossil evidence in that they provide snapshots in time, typically representing a few hours or days, a resolution we tend not to get from other records."

Researchers were able to identify a number of animals from the footprints, including elephants, horses, and camels.

The presence of elephants was particularly notable, as these large animals appear to have gone locally extinct in the Levant by around 400 thousand-years-ago.

"The presence of large animals such as elephants and hippos, together with open grasslands and large water resources, may have made northern Arabia a particularly attractive place to humans moving between Africa and Eurasia," said Michael Petraglia of Max Planck Institutes for the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH).

The dense concentration of footprints and evidence from the lake sediments suggests that animals may have been congregating around the lake in response to dry conditions and diminishing water supplies.

Humans, too, may have been utilising the lake for water and the surrounding area for foraging.

"We know people visited the lake, but the lack of stone tools or evidence of the use of animal carcasses suggests that their visit to the lake was only brief," said Stewart.

Human movements and landscape use patterns, therefore, may have been closely linked to the large animals they shared the area with.

These findings suggest that human movements beyond Africa during the last interglacial period -- a time of relatively humid conditions across the region -- extended into northern Arabia, highlighting the importance of Arabia for the study of human prehistory.

(With IANS Inputs)