Washington: A surprising hot spot of the potent global-warming gas methane hovers over part of the southwestern U.S., according to satellite data.

That result hints that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and other agencies considerably underestimate leaks of methane, which is also called natural gas.

The higher level of methane is not a local safety or a health issue for residents, but factors in overall global warming. It is likely leakage from pumping methane out of coal mines.

While methane isn't the most plentiful heat-trapping gas, scientists worry about its increasing amounts and have had difficulties tracking emissions.

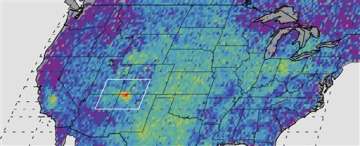

A satellite image of atmospheric methane concentrations over the continental U.S. shows the hot spot as a bright red blip over the Four Corners area of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona and Utah. The image used data from 2003 to 2009.

Within that hot spot, a European satellite found atmospheric methane concentrations equivalent to emissions of about 1.3 million pounds a year. That's about 80 percent more than the EPA figured. Other ground-based studies have calculated that EPA estimates were off by 50 percent.

The methane concentration in the hot spot was more than triple the amount previously estimated by European scientists.

The new study, done by NASA and the University of Michigan, was released Thursday by the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The amount of methane in the Four Corners—an area covering about 2,500 square miles—would trap more heat in the atmosphere than all the carbon dioxide produced yearly in Sweden. That's because methane is 86 times more potent for trapping heat in the short-term than carbon dioxide.

“It's the largest signal we can see from the satellite,” said study lead author Eric Kort, a University of Michigan atmospheric scientist. “It's hard to hide from space.”

There could be some areas elsewhere in the country where more methane is emitted if it is dispersed by wind, Kort said.

Kort said the methane likely comes from leaks as workers extract natural gas from coal beds, and not from hydraulic fracturing, called fracking, because the data were collected before fracking really caught on.

The results were so initially surprising to the scientists that they waited several years and then used ground monitors to verify what they saw from space, Kort said.

Several methane experts said the research makes sense to them and that the detected methane amount is disturbing.

“That is immense,” Terry Engelder, a scientist at Pennsylvania State University, wrote in an email.

Latest World News