WATCH! NASA's Cassini spacecraft finds flooded canyons on Saturn's moon Titan

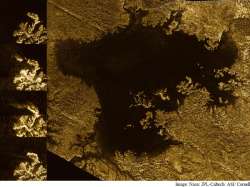

Scientists have found that some of the steep-sided canyons on Saturn's largest moon Titan are flooded with liquid hydrocarbons, based on the radar observation by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Such features on Saturn’s largest moon

Scientists have found that some of the steep-sided canyons on Saturn's largest moon Titan are flooded with liquid hydrocarbons, based on the radar observation by NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

Such features on Saturn’s largest moon provides researchers with the opportunity to better understand Titan’s origins.

"The finding represents the first direct evidence of the presence of liquid-filled channels on Titan, as well as the first observation of canyons hundreds of meters deep," Xinhua quoted NASA as saying.

The discovery was based on data collected from a close flyby Cassini made over Titan in May 2013, during which the spacecraft's radar instrument focused on channels that branch out from the moon' s second largest hydrocarbon sea Ligeia Mare.

Previously, the branching channels appear dark in radar images, much like Titan's methane-rich seas, but it was not clear if the dark material was liquid or merely saturated sediment, which at Titan's frigid temperatures would be made of ice, not rock.

So during the 2013 pass, the Cassini spacecraft pinged the surface of Titan with microwaves, and the returned signals indicated the surface of the channels is extremely smooth, meaning they are currently liquid filled.

The Cassini observations also revealed that the channels - in particular, a network of them named Vid Flumina - are narrow canyons, generally a bit less than a kilometre wide, with slopes steeper than 40 degrees.

The canyons also are quite deep with those measured 790 to 1, 870 feet (240 to 570 meters) from top to bottom, Nasa said.

The presence of such deep cuts in the landscape might be the result of uplift of the terrain, or changes in sea level, or perhaps both.

"It is likely that a combination of these forces contributed to the formation of the deep canyons, but at present it is not clear to what degree each was involved," said Valerio Poggiali of the University of Rome, a Cassini radar team associate and lead author of the study.

"What is clear is that any description of Titan's geological evolution needs to be able to explain how the canyons got there," Poggiali added.

The findings have been published in the US journal Geophysical Research Letters.

(With agency inputs)