People continue to disappear in Pakistan for criticizing military: Pak watchdog

The damning report card issued by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan says people continue to disappear in Pakistan, sometimes because they criticize the country’s powerful military or because they advocate better relations with neighboring India.

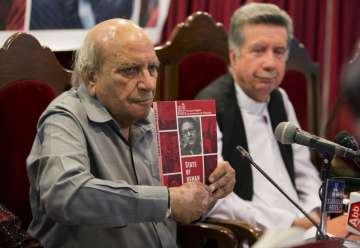

An independent Pakistani watchdog criticized the country’s human rights record over the past year in a new report released Monday, saying the nation has failed to make progress on a myriad of issues, ranging from forced disappearances, to women’s rights and protection of religious minorities.

The damning report card issued by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan says people continue to disappear in Pakistan, sometimes because they criticize the country’s powerful military or because they advocate better relations with neighboring India.

The controversial blasphemy law continues to be misused, especially against dissidents, with cases in which mere accusations that someone committed blasphemy lead to deadly mob violence, it said.

While deaths directly linked to acts of terrorism declined in 2017, the report says attacks against the country’s minorities were on the rise.

The 296-page report was dedicated to one of the commission’s founders, Asma Jahangir, whose death in February generated worldwide outpouring of grief and accolades for the 66-year-old activist who was fierce in her commitment to human rights.

“We have lost a human rights giant,” U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres said following Jahangir’s death. “She was a tireless advocate for inalienable rights of all people and for equality - whether in her capacity as a Pakistani lawyer in the domestic justice system, as a global civil society activist, or as a Special Rapporteur ... Asma will not be forgotten.”

Monday’s report also took aim at religious bigotry in Pakistan and the government’s refusal to push back against religious zealots, fearing a backlash.

“Freedom of expression and freedom of association is under attack, except for those who carry the religious banner,” commission spokesman I.A. Rehman said at the release of the report, which accused Pakistani authorities of ignoring “intolerance and extremism.”

Religious conservative organizations continue to resist laws aimed at curbing violence against women, laws giving greater rights to women and removing legal restrictions on social exchanges between sexes, which remain segregated in many parts of Pakistani society, it said.

Still, there was legal progress in other areas, it noted, describing as a “landmark development” a new law in the country’s largest province, Punjab, which accepts marriage licenses within the Sikh community at the local level, giving the unions protection under the law.

But religious minorities in Pakistan continued to be a target of extremists, it said, citing attacks on Shiites, Christians falsely accuse of blasphemy and also on Ahmedis, a sect reviled by mainstream Muslims as heretics. Ahmedis are not allowed under Pakistan’s constitution to call themselves Muslims.

“In a year when freedom of thought, conscience and religion continued to be stifled, incitement to hatred and bigotry increased, and tolerance receded even further,” said the report.

On Sunday in Quetta, the capital of southwestern Baluchistan province, gunmen attacked Christian worshippers as they left Sunday services, killing two. Five other worshippers were wounded, two seriously.

Last year was a troubling year for activists, journalists and bloggers who challenged Pakistan’s military. Several were detained, including five bloggers who subsequently fled the country after their release. From exile, some of them said their captors were agents of Pakistan’s intelligence agency, ISI. The agency routinely refuses to comment on accusations it is behind the disappearances. The bloggers were also threatened with charges of blasphemy.

In December, Raza Mehmood Khan, an activist who worked with schoolchildren on both sides of the border to foster better relations was picked up by several men believed to be from the ISI after leaving a meeting that criticized religious extremism.

In recent weeks, Pakistan’s Geo Television has been forced off the air in much of the country. Many activists have blamed this on the military, which took umbrage when the outlet criticized the country’s security institutions.

Last year, a government-mandated commission on enforced disappearances received 868 new cases, more than in two previous years, the report said. The commission located 555 of the disappeared but the remaining 313 are still missing.

“Journalists and bloggers continue to sustain threats, attacks and abductions and blasphemy law serves to coerce people into silence,” the report said.