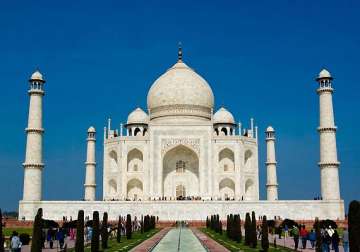

Environment Day: Agra seems to have lost the battle to pollution

Agra, June 5: Even after 20 years of judicial activism, major policy pronouncements and projects worth millions of rupees, this Taj city remains pock-marked with mounds of garbage. Air and water pollution threaten the health

Agra, June 5: Even after 20 years of judicial activism, major policy pronouncements and projects worth millions of rupees, this Taj city remains pock-marked with mounds of garbage. Air and water pollution threaten the health of people and the world famous monuments that is visited by millions of tourists every year.

In 1993, disposing of a public suit filed by eco-lawyer M.C. Mehta, a Supreme Court bench headed by Justice Kuldip Singh ordered far-reaching structural changes to make the 10,000 sq km eco-sensitive Taj Trapezium Zone safe for the Taj Mahal. The measures to be taken were based on the 20-odd recommendations of a high-powered committee headed by eminent scientist S. Varadarajan.

Twenty years later, newspaper headlines frequently read: "Taj tilting" or "Taj yellowing," NGO functionary Vinay Paliwal pointed out to IANS.

D.K. Joshi, a member of the Supreme Court monitoring committee, says: "The top officials of various departments have collectively played a crude joke on Agra. We neither have water, nor power; the sewage system does not work, community ponds have disappeared; trees have been chopped up; and the Yamuna river continues to wail and scream. Nothing has changed, conditions have worsened."

The chemical laboratories of the Archaeological Survey of India in Agra suggest that the suspended particulate matter (SPM) level annually averages around 400 micrograms per cubic metre, against the safe level of 100.

The SPM rises as the river bed runs dry and the Rajasthan desert gradually expands into Uttar Pradesh. In recent years, there has also been large-scale mining in the Aravali ranges, pushing up particulate matter in the air.

Agra Water Works uses more chemicals and gases than the stipulated safe limits prescribed by WHO. This is because there is not enough raw water to process in the Yamuna. "When there is no fresh water in the river, what we process is really sewage and effluents that flow down to Agra," an official of the city Jal Sansthan said, seeking anonymity for obvious reasons.

Community ponds have run dry and even wells have no water in them.

B.B. Awasthi, regional officer of the UP State Pollution Control Board, told IANS that the sulphur dioxide levels in city air had reduced: "Against 15 micrograms earlier, it is now below five micrograms. The large-scale use of CNG has been helpful."

Awasthi said if the city was assured of regular power supply, the use of more than 100,000 diesel generators would automatically come down, bringing down the nitrogen oxide levels.

As for water, the situation is not very different from 1996, he said.

"Against an installed capacity of 154 million litres daily, the three Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) treat not more than 80 MLD (million litres per day) and that too, not sewage but nullah (drain) water."

When the Supreme Court bench in 1996 ordered a series of restrictions and projects to cut down environmental pollution in the Taj Trapezium, there were people who worried that labour would be displaced and economic growth affected.

Mohan Khandelwal, former president of the Taj Trapezium Udhyog Sangharsh Samiti, which led the movement against the shifting of industries from Agra, told IANS: "Local industries had no role in adding to the pollution load, but were victimised, while the Mathura Oil Refinery was spared."

Two decades after the judgment, Khandelwal says, "the situation is actually worse, going by pollution control board data. The Yamuna is a sewage canal, and increased traffic means heightened air pollution. The recommendations of the S. Varadarajan committee have been forgotten."

The apex court wanted several rows of trees on the western periphery of the city to filter the dust-laden westerlies that blow in from from Rajasthan. That has not happened and greenery here has all but vanished as tall buildings now stand where community ponds once were.

District Forest Officer N.K. Janoo, however, says that the green cover has increased by nearly two percent.

"Green coverage in the district has increased by 0.5 percent, while in the city it has gone up to 14 percent. The SPM level has come down in the vicinity of the Taj Mahal by a good 19 percent, as broad-leaved trees line the roads and habitations. Agra Cantonment has the largest green belt. The Yamuna Kinara road is lined with saplings."

Activists like Surendra Sharma, however, say the war on pollution here is as good as lost. Given that authorities are still to even acknowledge the problem, the question, perhaps, is whether that war ever began.

In 1993, disposing of a public suit filed by eco-lawyer M.C. Mehta, a Supreme Court bench headed by Justice Kuldip Singh ordered far-reaching structural changes to make the 10,000 sq km eco-sensitive Taj Trapezium Zone safe for the Taj Mahal. The measures to be taken were based on the 20-odd recommendations of a high-powered committee headed by eminent scientist S. Varadarajan.

Twenty years later, newspaper headlines frequently read: "Taj tilting" or "Taj yellowing," NGO functionary Vinay Paliwal pointed out to IANS.

D.K. Joshi, a member of the Supreme Court monitoring committee, says: "The top officials of various departments have collectively played a crude joke on Agra. We neither have water, nor power; the sewage system does not work, community ponds have disappeared; trees have been chopped up; and the Yamuna river continues to wail and scream. Nothing has changed, conditions have worsened."

The chemical laboratories of the Archaeological Survey of India in Agra suggest that the suspended particulate matter (SPM) level annually averages around 400 micrograms per cubic metre, against the safe level of 100.

The SPM rises as the river bed runs dry and the Rajasthan desert gradually expands into Uttar Pradesh. In recent years, there has also been large-scale mining in the Aravali ranges, pushing up particulate matter in the air.

Agra Water Works uses more chemicals and gases than the stipulated safe limits prescribed by WHO. This is because there is not enough raw water to process in the Yamuna. "When there is no fresh water in the river, what we process is really sewage and effluents that flow down to Agra," an official of the city Jal Sansthan said, seeking anonymity for obvious reasons.

Community ponds have run dry and even wells have no water in them.

B.B. Awasthi, regional officer of the UP State Pollution Control Board, told IANS that the sulphur dioxide levels in city air had reduced: "Against 15 micrograms earlier, it is now below five micrograms. The large-scale use of CNG has been helpful."

Awasthi said if the city was assured of regular power supply, the use of more than 100,000 diesel generators would automatically come down, bringing down the nitrogen oxide levels.

As for water, the situation is not very different from 1996, he said.

"Against an installed capacity of 154 million litres daily, the three Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) treat not more than 80 MLD (million litres per day) and that too, not sewage but nullah (drain) water."

When the Supreme Court bench in 1996 ordered a series of restrictions and projects to cut down environmental pollution in the Taj Trapezium, there were people who worried that labour would be displaced and economic growth affected.

Mohan Khandelwal, former president of the Taj Trapezium Udhyog Sangharsh Samiti, which led the movement against the shifting of industries from Agra, told IANS: "Local industries had no role in adding to the pollution load, but were victimised, while the Mathura Oil Refinery was spared."

Two decades after the judgment, Khandelwal says, "the situation is actually worse, going by pollution control board data. The Yamuna is a sewage canal, and increased traffic means heightened air pollution. The recommendations of the S. Varadarajan committee have been forgotten."

The apex court wanted several rows of trees on the western periphery of the city to filter the dust-laden westerlies that blow in from from Rajasthan. That has not happened and greenery here has all but vanished as tall buildings now stand where community ponds once were.

District Forest Officer N.K. Janoo, however, says that the green cover has increased by nearly two percent.

"Green coverage in the district has increased by 0.5 percent, while in the city it has gone up to 14 percent. The SPM level has come down in the vicinity of the Taj Mahal by a good 19 percent, as broad-leaved trees line the roads and habitations. Agra Cantonment has the largest green belt. The Yamuna Kinara road is lined with saplings."

Activists like Surendra Sharma, however, say the war on pollution here is as good as lost. Given that authorities are still to even acknowledge the problem, the question, perhaps, is whether that war ever began.