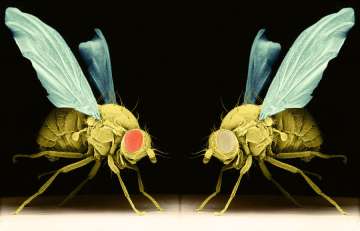

United States: Using fruit flies as a traumatic brain injury (TBI) model may help researchers identify important genes and pathways that promote the repair of and minimise damage to the nervous system, a new study suggests.

“Fruit flies actually have a very complex nervous system,” said Kim Finley from San Diego State University (SDSU) in the US.

“They are also an incredible model system that has been used for over 100 years for genetic studies, and more recently to understand the genes that maintain a healthy brain,” said Finley.

In humans, changes in mood, headaches and sleep problems are just a few of the possible symptoms associated with suffering mild TBI, researchers said.

The timeline for these symptoms can vary greatly - some people experience them immediately following injury, while others may develop problems many years after, they said.

According to Finley, because fruit flies grow old quickly, observing them allows researchers to rapidly study the long-term consequences of traumatic brain injury.

“Traits that might take 40 years to develop in people can occur in flies within two weeks,” she said.

To test whether flies can be used to model traumatic brain injuries, researchers used an automated system to vigorously shake and traumatise thousands of fruit flies.

“Fruit flies come out of this mild trauma and appear perfectly normal,” said Eric Ratliff from SDSU.

“However, the flies quickly begin to show signs of decline, similar to problems found in people who have been exposed to head injuries,” he said.

In the study, injured fruit flies showed damage to neurons within the brain, as well as an accumulation of a protein called hyper-phosphorylated Tau, a hallmark feature of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), researchers said.

Injured flies also began to experience insomnia and their normal sleep patterns deteriorated. The results suggest that studying traumatic injury in fruit flies may uncover genetic and cellular factors that can improve the brain’s resilience to injuries, they said.

“It is really a unique model. We have developed it to be reliable, inexpensive and fast,” said Finley.

TBIs occur most frequently from falling, but can also result from military combat, car accidents, contact sports or domestic abuse, researchers said.

The findings were published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.