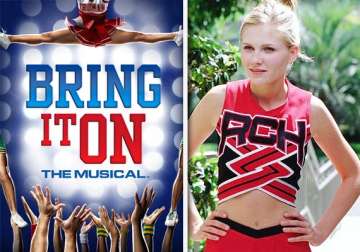

Writers Guild Files Claim Against 'Bring It On: The Musical'

Los Angeles, Aug 15: Citing the guild agreement's “separated rights” provisions, the union is seeking to enjoin the new play and obtain damages on behalf of the screenwriter of the 2000 movie that began the

Los Angeles, Aug 15: Citing the guild agreement's “separated rights” provisions, the union is seeking to enjoin the new play and obtain damages on behalf of the screenwriter of the 2000 movie that began the franchise.

In a move that could shut down a high-profile musical on the eve of its national tour, the Writers Guild of America has filed a claim over Bring It On: The Musical on behalf of Jessica Bendinger, the screenwriter of the 2000 Universal film on which it is based, The Hollywood Reporter has learned.

The confidential arbitration demand, filed a week ago, asserts that Beacon Communications Corp. and Beacon Communications, LLC are exploiting Bendinger's dramatic rights in the cheerleader-themed Bring It On without her consent, in violation of the guild agreement's “separated rights” provisions. It seeks damages and an injunction against Bring It On: The Musical, which is being coproduced by Universal Pictures Stage Productions, Beacon Communications and others.

Beacon's outside counsel for the matter, Alan Brunswick of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, tells THR, “The claim is without merit. We will vigorously defend it.”

In an interview, Bendinger counters that “Imitation is not the sincerest form of flattery. Compensation is.”

The screenwriter says she first heard about the show “in the worst way.” She had been working on a stage version of her own for six years and was developing the project with former Universal production chief Marc Platt, producer of the Broadway hit Wicked. But then she learned that a New York theater attorney not affiliated with her had been heard to say at a cocktail party that he was shopping the theatrical rights to the movie – the same rights she had been seeking to exploit.

The play subsequently opened for previews in Atlanta earlier this year. It's scheduled to begin a four-city national tour in Los Angeles on October 30.

“I was shocked,” Bendinger says. “A writer works all her life trying to have a first hit. I was not treated well, given the revenue stream I created for them.”

The film, which grossed $90 million worldwide, stars Kirsten Dunst and inspired four direct to video followups. The three most recent video outings logged $18 million to $24 million in sales each, according to the-numbers.com, but Bendinger did not share in the revenue.

Her case “underscores the horrors of being a successful writer in Hollywood,” says her attorney, Neville Johnson of Johnson & Johnson. After cutting her out of the film franchise she created, the company, in Bendinger's view, is taking the same approach to the stage production.

“It feels like they thought they could just keep going,” she says.

Both Bendinger and Johnson praise the WGA for bringing the case. The arbitration could begin in several weeks, or might not start for several months, depending on the availability of the arbitrator. With the play scheduled to open in two and a half months, it's unclear whether the guild's request for an injunction will have any practical effect until the case is heard and decided.

A key issue in the case is expected to be the relationship between Bendinger's screenplay and the stage play: even though the titles are similar, is the play indeed a stage version of the movie or not?

The guild agreement's separated rights provisions delineate various rights that are reserved to screen and television writers under specified circumstances. The section is notoriously intricate – it sprawls across dozens of pages – but for all their detail, the clauses don't clearly explain how to determine whether a stage production is or is not an exploitation of the dramatic rights in the original film.

Complicating matters, separated rights relate to the original movie's “story,” not its screenplay. “Story” is defined in the guild agreement as “literary or dramatic material indicating the characterization of the principal characters and containing sequences and action suitable for use in, or representing a substantial contribution to, a final script.”

That's more skeletal than a screenplay itself, which may give the WGA room to maneuver even if the movie and stage play have different plots,as a comparison of the film's website and a newspaper review of the play suggest may be the case.

A 2000 arbitration decision involving a scripted Universal theme park show based on Waterworld touched on the issue, saying that where “the story of the Picture and the (theme park show) is substantially the same,” the live show represents an exploitation of dramatic rights in the original rather than an exploitation of sequel rights. However, the arbitrator didn't explain how he arrived at that formulation, nor whether it was intended as a definitive explanation.

The writer prevailed in the Waterworld case, leading to a confidential settlement.

Arbitration decisions are not public, and it's not known whether relevant cases have arisen since then. The decisions are also not technically binding as precedent, although they are routinely used as such.